By: Hilda M. Ortiz, Nancy P. Mejia, and Sarai Arpero of Latino Health Access

Program Context: Public health continues to move toward a holistic community approach. This transition requires the participation of historically marginalized populations in policy, systems, and environmental work to address the social determinants of health that perpetuate health disparities. Equity has become a buzzword in the field. However, to truly achieve equity, it is necessary to analyze the history of disinvestment in marginalized communities and the importance of their participation and leadership in creating sustainable change.1 The Community Health Worker, or Promotor, model can be an effective strategy in health education and disease prevention by fostering lasting relationships of trust and messaging within and between communities.2 Over the last twenty-five years, promotores at Latino Health Access (LHA) in Santa Ana, CA have successfully helped community members to transition from recipients of services to agents of change. But, in today’s context, how can organizations be intentional about supporting this type of resident engagement through promotores? What mechanisms within organizations help promotores to undertake community work through an equity lens? How is this work achieved in the context of service grants that require reporting-based service outcomes? Our case study responds to these questions.

Program Design: This case examines a capacity building program that included a residential training and field-based coaching support, intended to transition promotores and supervisors from just service providers to agents of long-term policy, systems, and environmental change. Promotores are community leaders that have been trained to provide basic health education and promotion. Latino Health Access staff, including the Director of Community Engagement and Advocacy (CEA) and promotores, designed the training curriculum and implementation coaching. The curriculum and the model for implementation were based on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Healthy Cities Framework, which stresses the value of place and social context in promoting health and wellbeing. The Healthy Cities framework consists of three main components in creating healthy environments: multi-sectoral collaboration, community engagement, and the use of data.3 The three components of the framework themselves contribute to addressing social determinants of health; however, this co-training program uses the framework with an equity approach, amplifying the community engagement piece as a central strategy.

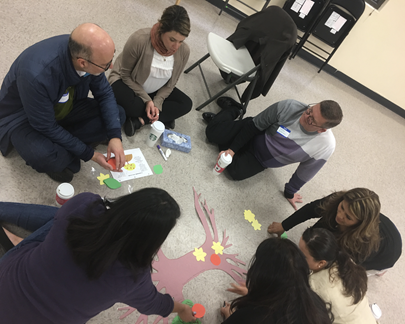

Picture 1. A team of promotores and administrative staff at a cohort training create a “Community Tree of Life” to identify the strengths of their community before developing strategies for community engagement based on those strengths

Promotores from four organizations representing low-income communities of color in Pennsylvania, California, and Colorado participated in the program. They were challenged to analyze the health issues affecting their communities’ health outcomes, increasing awareness about social determinants of health and expanding their understanding of health beyond individual medical care. Subsequently, participants from each organization identified an area of focus in their community based on their organizations’ past work, health outcomes and health disparities. Participants used data disaggregated to the smallest geographic level available to identify health inequities amongst populations that are traditionally left out. This point is critical in designing a program that is inclusive, especially when we speak of transforming places and social contexts where conditions can vary at the block level.4

The training guided participants to analyze problems, solutions, and impact at individual, family, community, and policy levels. Participants then analyzed the root causes of the needs, focusing on the social determinants of health and the importance of upstream solutions, in order to make a larger and more sustainable impact and to bridge their service approach to policy advocacy.

Diagram 1. Example of an analysis of problems and solutions at different levels, showcasing the importance of a comprehensive approach that includes services and advocacy.

Coaching and training activities challenged participants to analyze the impact and sustainability of advocacy campaigns in which community members play a passive role. Participants analyzed this both from a promotor standpoint (as a member of the same community) and as an administrator representing organizations with the opportunity to expand inclusive leadership. Additionally, conversations addressed the challenges that promotores experience developing the leadership of residents who live in environments that generate negative health outcomes and, therefore, who continue to require services. Rather than a challenge, these contexts can be opportunities to further increase awareness about the inequities that entire communities are facing and to connect residents to advocacy campaigns.

Following the initial training, LHA CEA staff supported participants from each organization as they partnered with their communities to develop a policy action plan. Additional trainings were provided, covering various topics such as basic knowledge of government and policy systems and analysis of case studies.

A large component of the program consisted of peer coaching between promotor teams and administrative staff. During peer coaching sessions, promotores supported each other to develop skills to carry out community meetings. Promotores played a facilitator role in these meetings by promoting conversations and increasing awareness through engaging participant in critical thinking as opposed to a more traditional didactic approach to health education. Similarly, administrative staff shared ways of designing organizational and team structures that invite promotores to raise and defend solutions proposed by the community as a way of holding the organization accountable for implementing community-led initiatives. Feedback processes and changes in organizational structure required to support promotores in advocacy work were also constantly visited and reflected on. During this process, promotores brought to the table the realities affecting the community and ensured project interventions were aligned with community priorities.

Picture 2. Cohort promotores tour a Wellness Corridor in Santa Ana hosted by Latino Health Access promotoras that detail the advocacy process for the project.

Program Impact: By integrating this strategy, each organization was able to capacitate a team of 5-8 promotores and 2-3 administrative staff to launch a policy advocacy campaign with their service base. Overall, the trainings and coaching served to walk teams through the process of using the same outreach and engagement strategies they have traditionally used, but changing the nature of the exchange between promotor and community member from a service transaction to a partnership. In one of the organizations, for example, promotores were able to use their services to begin creating relationships with community members and bring them together to have conversations about improvements that they identified within their neighborhood, such as addressing trash, broken street lights and lack of sidewalks to improve safe pathways for children to get to school.

Together, they organized a neighborhood clean-up exercise named the Hope and Energy project, a short-term solution that raised awareness and induced action toward long-term policy change. The promotores facilitated meetings with local city council members and city staff and the project grew into an advocacy campaign to dedicate transportation funding to modifying street infrastructure to promote physical activity (cycling, walking, and public transit). The resident groups provided public comment during City Council meetings, met with City engineers and with councilmembers. By establishing these relationships with key decision makers, they were able to redirect funding to their neighborhood for sidewalk and bike lane improvements.

Lessons Learned

- Convincing people that community members can transform from passive recipients of services to guiding leaders for change is one of the most significant challenges. This transformation challenges decision-making processes and the role that promotores play within the organization.

- Peer-to-peer support between supervisors and promotores facilitate the process, acknowledging the experiences and knowledge in a co-training approach.

- This new strategy should be integrated into an organization’s current focus, rather than disregarding the reputation of trust that has been created with each organization’s community.

- Promotores and supervisors require constant accompaniment through a process that entails a shift in the overall approach to achieve health equity- going from service providers to advocates.

- To decentralize leadership and center the most vulnerable sectors in decision making processes, organizations need to build the capacity of promotores to identify and promote leaders in their communities.

Sustainability and Scale-up:The model places promotores in positions where they can incorporate on-the-ground lessons into organizational solutions and allows cross-trainings internally with supervisors and externally with partners. A next step in implementation of the model will be to create new opportunities to expand learning and galvanize higher-level action and change through increased collaboration with multi-sectoral stakeholders as outlined in the Healthy Cities Framework. Ultimately, implementation of this model beyond the community level (i.e. county, state level) could further address the root causes of health disparities.

Sources

1 Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2008. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health.

2 Balcazar, H., Rosenthal, E. L., Brownstein, J. N., Rush, C. H., Matos, S., & Hernandez, L. (2011). Community Health Workers Can Be a Public Health Force for Change in the United States: Three Actions for a New Paradigm. American Journal of Public Health, 101(12), 2199–2203. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300386

3 World Health Organization (2018). Healthy Cities. Retrieved from http://www.wpro.who.int/health_promotion/about/healthy_cities/en/

4 PolicyLink (2018). Counting a Diverse Nation: Disaggregating Data on Race and Ethnicity to Advance a Culture of Health.

Leave a Reply